A new report from the ACLU, using the most recent federal data collected by the U.S. Department of Education in 2015-16, found that:

- 1.7 million students are in schools with police but no counselors.

- 3 million students are in schools with police but no nurses.

- 6 million students are in schools with police but no school psychologists.

- 10 million students are in schools with police but no social workers.

These numbers are sickening, literally, when you consider the negative health impact on on students without access to proper mental and physical healthcare–in addition to the trauma caused by police in the schools. The report goes on to explain how students of color are the most over policed, writing,

The use of police in schools has its roots in the fear and animus of desegregation. Students of color are more likely to go to a school with a law enforcement officer, more likely to be referred to law enforcement, and more likely to be arrested at school. Research also demonstrates that students who attend schools with high percentages of Black students and students from low-income families are more likely face security measures like metal detectors, random “contraband” sweeps, security guards, and security cameras, even when controlling for the level of misconduct in schools or violence in school neighborhoods.

In the midst of these upside down–and racist–priorities, Teaching for Black Lives, a new book from Rethinking Schools, is helping to transform the conversation about race and education. The book features teaching activities to engage students in discussions about mass incarceration, youth jails, police violence–as well as Black excellence and the many important societal contributions of African Americans.

Thousands of teachers around the country used curriculum from the book during the national Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action, which had as one of its demands, “Fund Counselors, Not Cops.” Educators from Durham, North Carolina to Denver, Colorado are doing a deep dive into the curriculum with study groups.

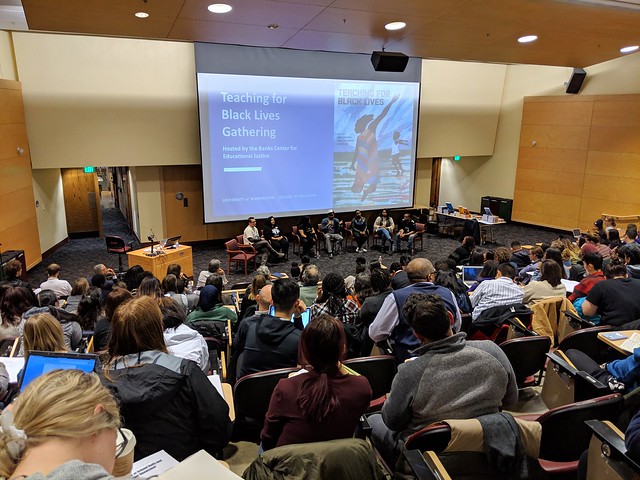

In Seattle, the University of Washington’s Banks Center for Educational Justice recently held a Teaching for Black Lives Forum hosted by the director of the program, Django Paris. The event featured, Jennifer Dunn Charlton, Wayne Au, Janelle Gary, Ke’Von Avery, Chardonnay Beaver, Sebrena Burr, and Jesse Hagopian.

Below is the news segment from Jesse Hagopian about the over policing of youth, Teaching for Black Lives, as well as the video and story of the University of Washington event.

Here’s today’s lesson plan for Black lives: Watch the videos, read the book, teach against anti-Blackness.

Jesse Hagopian joins Q13 Fox News to talk about Teaching for Black Lives

—

“Teaching for Black Lives” gathering spreads message of strength

The work we do, we do in community. Then it doesn’t feel like work.

Finding the strength to make change, push for truth and walk with heads held high was the message of last week’s “Teaching for Black Lives” event.

Hosted by the University of Washington’s Banks Center for Educational Justice, the gathering of current teachers, future teachers and community members listened to the experiences of Black students and their allies.

“Teaching for Black Lives,” a collection of writings to offer guidance in connecting curriculum, teaching and policy to Black students on a personal level, formed the basis of this deeper discussion.

One of the book’s editors, Jesse Hagopian (MIT ‘06), gave example after example of physical and mental abuse of Black students, each one drawing more grieved responses from the audience.

“We have to defend their bodies, and we have to defend their minds, and we’ve put together a curriculum to help do that,” said Hagopian, who teaches ethnic studies and is co-advisor to the Black Student Union at Seattle’s Garfield High School, among other roles.

Ke’Von Avery, one of three Garfield seniors speaking at the event, said that going through high school and not finding yourself in the curriculum is an outrageous experience. He explained that Black history was absent from textbooks and the core curriculum.

A quote Avery shared from “Teaching for Black Lives” spoke of the necessity of examining oneself, whether a teacher or someone outside the school system, and seeing what needs to be changed. A poem in the book described the way students are effectively taking two sets of notes in class—what they’re taught and their own history that differs from the primary narrative.

“We love this book,” Avery said. “It speaks to us and our experience and our truth.”

In the midst of describing the challenges they and their peers face, the students still drew attention to the hope that exists.

Janelle Gary shared an African saying that translates to “Help me and let me help you.” She interprets it as speaking to the power in building shared knowledge.

“The work we do, we do in community,” Jennifer Dunn Charlton said. “Then it doesn’t feel like work, it feels like—well, a soul force.”

Charlton has taught social studies at multiple Seattle high schools and currently works with the Center for Racial Equity as a presenter and curriculum writer.

The soul force she referred to comes from part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech. She read a portion which spoke of acting with dignity and discipline, protesting creatively instead of with physical violence and of rising “to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.”

Wayne Au, co-editor of “Teaching for Black Lives” and a professor at UW Bothell, brought to life the story of the John Muir Elementary School welcome event that continued despite opposition and prompted educators at other Seattle schools to seek policy change. Teachers nationwide began to plan similar events, and the day of welcome turned into an annual Week of Action.

“I think educators are showing us how to struggle and how to win,” Hagopian said. “Politics isn’t just waiting every four years to cast a ballot, but it’s you taking action.”

Yes! This is such important work! Thank you!!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Most Revolutionary Act and commented:

The use of police in schools has its roots in the fear and animus of desegregation. Students of color are more likely to go to a school with a law enforcement officer, more likely to be referred to law enforcement, and more likely to be arrested at school

LikeLike