A nation that can feed its billionaires but not its children has an economic system built to protect cruelty.

Originally published in Truthout.org

When school counselors must decide which children get to eat, it’s time to acknowledge we’re in a national affordability crisis. The problem is the economy itself — not just its current condition, but the underlying unfairness of how it is organized.

A friend recently told me a story that made this reality impossible to ignore. Her elderly parents live near an elementary school not far from the nation’s capital. For several years, they had been quietly raising money to provide groceries and basic supplies for families whose children were going hungry. When Republicans suspended SNAP benefits, the need surged overnight. What had been a steady act of care suddenly became an emergency response.

They gathered donations from grocery stores and community members and were able to support 102 children across four local schools. But more than twice that many needed help.

This meant that in the wealthiest nation on earth, school counselors — people trained to nurture children, not triage hunger — were conscripted into the role of deciding which children would eat and which children would be left to endure hunger. A nation that can feed its billionaires but not its children is not suffering from confusion; it is suffering from both a crisis of conscience and a system built to protect cruelty.

Teach Truth & Sing the Blues: Jesse’ Songbook for Survival is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And yet, even in the face of realities like this, we are still being told that there is not a widespread affordability crisis in America.

Recently, economist Allison Schrager, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, wrote an op-ed arguing that “there is not a widespread ‘affordability crisis’ in the U.S.,” suggesting that while some households are struggling, the economy is “positive for most Americans.” She acknowledges rising food, housing, health care, and childcare costs — but insists that because “real income growth is still positive for most Americans” the situation should not be described as a broad crisis. In her telling, what millions are experiencing is less a structural failure than a matter of sticker shock, a need to readjust expectations that are too high, or simply lingering anxiety. To reach those conclusions Schrager had to pointedly ignore a recent JPMorganChase Institute report showing that real income growth has slowed to near-decade lows, with median real income for prime-age workers rising only about 2 percent after inflation — and younger workers are seeing even weaker gains.

You can hear that same distance from reality echoed at the highest levels of government. During Donald Trump’s recent national address on the economy he falsely claimed that grocery prices were falling. In fact, grocery prices are up 2.7 percent over the past year, a meaningful increase for families already stretched thin. Electricity prices — conveniently absent from Trump’s speech — are up some 13 percent, driven in part by the explosive growth of energy-intensive data centers tied to his own push for rapid AI expansion. These costs do not disappear because they are omitted from a speech; they show up in monthly bills.

What makes MAGA politicians and economists like Schrager economic alchemists rather than social scientists is that they assess the economy from the vantage point of the comfort of their own prosperity, ignoring the evidence that working people create the nation’s wealth while the rewards are quietly captured by those already at the top. Schrager herself once lamented in a column, “I’m not nearly as rich as my Fidelity balance suggests.” When the greatest hardship you are facing is a tremor in your financial investment account, it becomes easy to declare that most people in the U.S. are doing fine.

But most people in this country do not live by Fidelity accounts. They live by their monthly bills. From New York City to Seattle, from sea to shining sea, the U.S. economy is starving the poor and stuffing the rich. In New York City during 2025, the median asking rent was about $3,599 a month, and rents now take roughly 55 percent of the typical household’s income, well above standard affordability thresholds. A February 2024 report showed 50 percent of households headed by Black people were housing insecure.

My hometown of Seattle, too, is one of the least affordable housing markets in the U.S., with rising home prices and rent. In the Seattle metro area, a household now needs to earn almost $92,000 a year just to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment, and rents for one- and two-bedroom apartments have risen more than 30 percent in just a few years. Additionally, fewer than 1 percent of homes for sale in the Seattle area are affordable to middle-income households. At the same time, Seattle is home to more than 54,000 millionaires, including 130 centimillionaires, and at least 11 billionaires. This contradiction is not accidental. It is engineered. Zoom out further, and the scale becomes impossible to ignore. Globally, the richest 1 percent hold more wealth than the bottom 95 percent of humanity combined.

Economic inequality is structural — and people are beginning to make that unmistakably clear at the ballot box.

In recent elections, openly socialist leaders like Seattle Mayor Katie Wilson and New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani won not by minimizing the problem, but by naming the affordability crisis directly and advancing a vision of bringing democracy into the economy. They spoke unapologetically about taxing extreme wealth, expanding public goods, and shifting power away from corporations and toward working people. Affordability is not a feeling. It is a monthly calculation. And for millions of families — including those children whose names were weighed and sorted by a school counselor — the numbers simply do not add.

Yet rather than confront the injustice at the heart of that reality, some insist the real mistake is believing fairness should matter at all. Schrager even recently wrote that “a lack of fairness actually powers the economy forward,” urging us to worry less about justice and more about growth.

We have reached the bleak moment when capitalism has grown so distorted, so grotesquely unequal, that even some of its most ardent defenders no longer bother pretending it is fair. They simply ask us to accept injustice as wisdom.

Maybe the first step toward fixing our affordability crisis is to send economists back to preschool. Preschoolers are taught that fairness matters. They are taught to share. They are taught that other people’s needs matter. These are the moral foundations of a humane society. Allison Schrager might benefit from sitting crisscross on a classroom rug and relearning them, instead of explaining to hungry families why their hardship is “efficient.”

Beyond re-enrolling some of our nation’s economists in preschool, the other imperative for addressing the affordability crisis is collective organizing — and, when necessary, strikes. When elites tell us that a “fixation on fairness” breaks government, they are really telling us whose lives they value least. Our task, then, is clear: organize society around solidarity and human need.

We’ve seen what a struggle for that kind of world has looked like before.

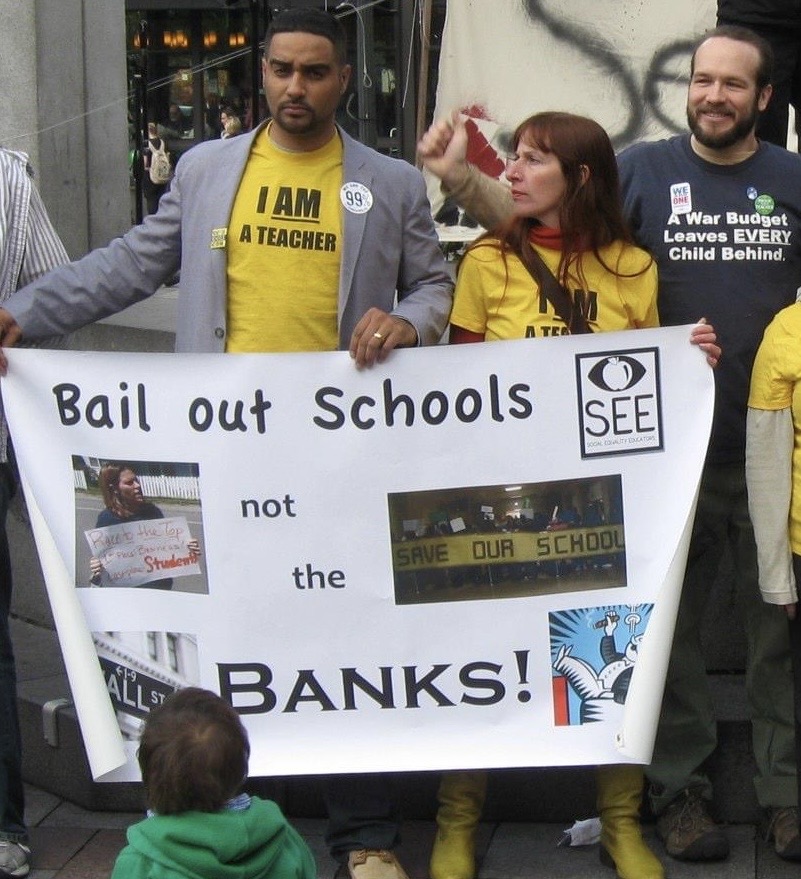

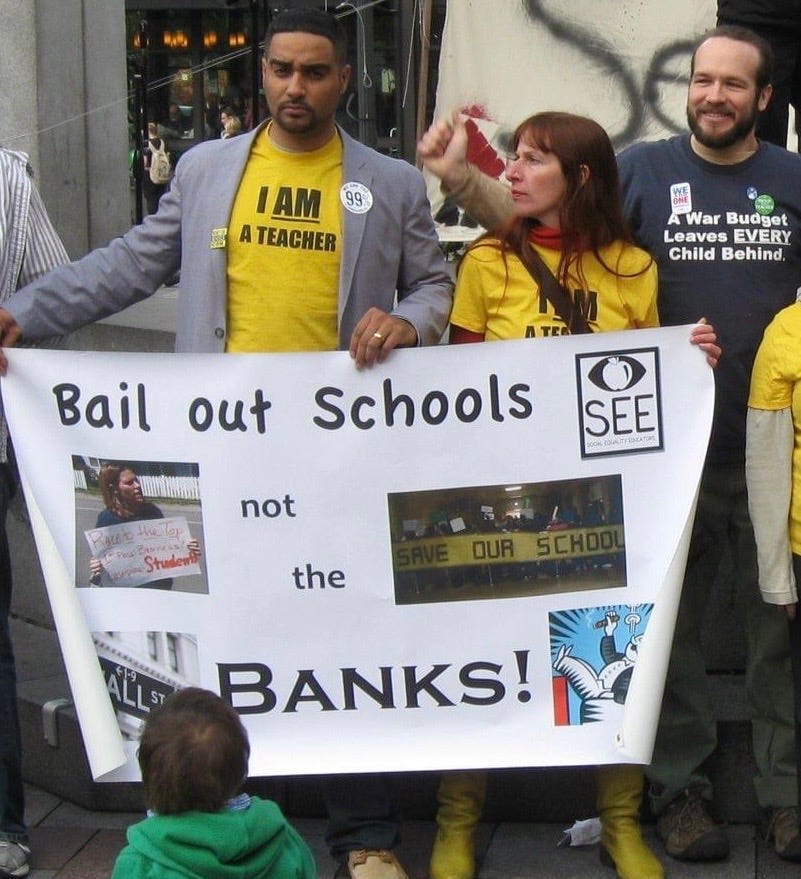

It was workers organizing that won the 8-hour workday, the weekend, child labor protections, Social Security, unemployment insurance, and the right to unionize. It was Black sanitation workers striking in Memphis, immigrant laborers walking out of fields and factories, teachers in West Virginia and Chicago refusing to quietly watch public goods collapse. More recently, strikes by auto workers, baristas, nurses, hotel workers, and Hollywood writers have secured better wages, safer conditions, and fairer contracts.

On January 23, 2026, unions and immigrant rights activists organized a general strike in Minneapolis to demand that ICE leave Minnesota and that the agent who killed legal observer Renee Good be prosecuted. As The Intercept reported, “Tens of thousands of Minnesotans braved extreme cold to march en masse and shuttered a reported 700-plus businesses in a daylong general strike with the support of all major unions.”

Workers walked off the job, schools closed, flights were disrupted, and downtown commerce ground to a halt. Unions representing teachers, nurses, telecom workers, hospitality workers, graduate employees, municipal workers, and stagehands coordinated walkouts and work stoppages — often maneuvering creatively around no-strike clauses by using sick time, safety provisions, and collective pressure on employers.

The result was a rare thing in American political life: a multi-sector shutdown that echoed the Minneapolis General Strike of 1934 and the “Day Without Immigrants” strike of 2006, demonstrating that when workers collectively withhold their labor, they can confront not only economic exploitation, but also state violence and rising authoritarianism.

The struggle for fairness is not naïve; it is the work of people who believe we deserve something better. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. understood this long before today’s affordability crisis. “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism,” he insisted, “but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country.”

Today, as millions struggle to afford rent, groceries, health care, and the basic conditions of a dignified life, they are rediscovering what King knew: Democratic socialism — an economy where workers democratically control the wealth they create — is fairness made real, both morally and materially.

###

Subscribe to Jesse Hagopian’s Substack, “Teach Truth and Sing The Blues,” to get all his latests posts.